3D Technical Combat System 1: Input Buffering and SOAP (Unity-Specific)

Input buffering for 3D does not differ much from the one for 2D. As I have discussed input buffering before, this post won’t go too much into the technical details.

By the way, this is the resulting product of the series (WIP)

It is difficult to see, but there are almost all features you can expect in a technical combat system - different combo routes, hitstops, just inputs (perfect inputs) etc. I intend to publish this on the Unity market store as a paid asset once complete.

Input Buffer

The information an input buffer needs for 3D is identical: buffer duration, keys, whether they are hold and how long they have been held for, and whether a key can be used for executing a command.

A (roughly) formalised class will look something like this:

class Key

{

int id;

bool stale; // If true, this key cannot execute a command

bool released;

bool initial; // Whether this key is pressed (or released) for the first time after being released (or pressed)

float duration; // int, if your system uses frames

}

Note on the Stale Field

It feels unnecessary to check whether a key can be used, as you might assume that all keys in the buffer may be used for executing a command. However, it turns out that this boolean flag is crucial for preventing misbehaviour.

Let’s imagine you are playing Street Fighter 6 as Ryu. As a stereotypical Ryu main, your neutral revolves around fireball zoning, random forwards jump and back jump into heavy sweep. As always, you try to open up your opponent with the classic fireball into forwards jump heavy punch. However, you accidentally input the fireball motion just before the heavy punch comes out.

As the fireball motion is still in the buffer, you might expect that the next punch attack on the ground causes the fireball to come out.

However, this doesn’t actually happen. In SF6, no matter how late a fireball motion is registered mid-air, if you successfully land an air normal attack after, your next ground attack does not convert into a special special attack.

Note that if I whiff the air normal, my ground punch turns into a fireball. This implies that the system marks all previous inputs as unusable for special attacks on hit to prevent accidental use of special attcks (This may not be true. I never looked at the source code). Note that not all games have this failure-proof feature.

Another example is Roman Cancel from Guilty Gear: Strive. The game seems to nullify any motion inputs registered prior to a RC, so it is not possible to perform 236236 moves by doing the first half before the RC and then the other half after.

Regardless, this field is necessary if the buffer window is large. The system may reuse the same input over and over until it is out of the buffer.

State Machine and Scriptable Objects

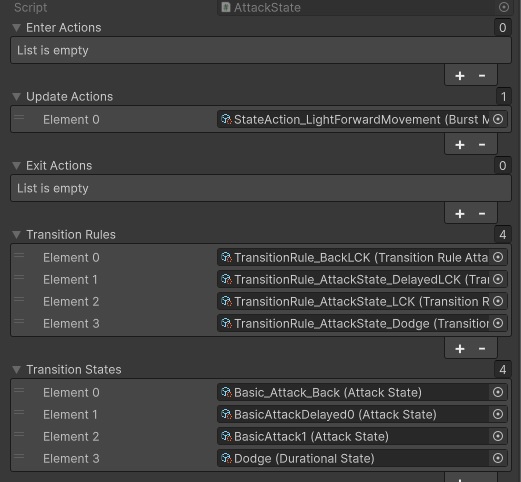

When it comes to adding motion inputs, you want to be as creative as it allows you to be (cough cough EWGF). The problem is, it is simply difficult to keep track of character states and the corresponding list of motion inputs that the player can perform in the current state. It becomes exponentially difficult to manage states if the player can enter the same state in different ways (such as just inputs leading to a superior state).

Scriptable objects workflow shines in situations like this. It allows for visualisation of relations through the exposure to the inspector and makes it possible to modify states without changing codes.

Scriptable Objects are not just for readonly data storage. It can be used to exchange data between multiple scripts. For example, if you want to implement perfect-frame execution mechanics, you can simply create a boolean scriptable object checking if the past input is done perfectly and upon entering the next state, check if that scriptable boolean is turned on.

This way, you can greatly simplify code interdependency and modulate the codebase.